Can’t decolonise the British military

SOAS receives £400,000 from Ministry of Defence for ‘cultural specialist’ trainings

The UK is the world’s second largest exporter of arms, the same £14bn a year as the UK’s annual aid budget. The UK has at least 20 military bases around the world—from Brunei to Belize, Kenya to Oman, the Ascension Islands in the Atlantic Ocean to the illegally occupied Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean. The British army is engaged in at least seven ‘covert wars’ in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria and Yemen. ‘Global Britain’s’ closest ally America has over 800 military bases around the world, making it the single greatest polluter in the world, more than 140 countries combined.1 Meanwhile in lecture rooms in Bloomsbury and army bases in Bedfordshire, the British armed forces are learning about the cultures, histories, religions and geographies of those countries in Regional Study Weeks “designed and delivered” on the Ministry of Defence’s behalf by the School of Oriental and African Studies. History repeats itself, while global war intensifies.

Training the military, exploiting Africa

|

| Force Troops Command structure: the DCSU operates under the 1st Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Brigade, alongside 13 other units of military intelligence |

Following Freedom of Information requests to both SOAS and the Ministry of Defence, Demilitarise SOAS can reveal that the university has received at least £400,000 since the end of 2016 to deliver Regional Study Weeks (RSW) on ‘Eastern Europe and Central Asia,’ ‘Middle East and North Africa,’ and ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’ to the Defence Cultural Specialist Unit (DCSU). These documents are publicly available here.

SOAS initially claimed they hadn't received any money from the MoD for these trainings, and refused to disclose any agendas or programmes of the trainings because it would "harm (SOAS') commercial interests" and "prejudice the university's ability to raise finances by exploiting its expertise in Asian and African affairs."

SOAS’s income from the MoD has increased fourfold in three years of running these trainings, which usually take place on campus, except the February 2018 ‘Sub-Saharan Africa Training Programme’ which was hosted at the Royal Air Force base at Henlow in Bedfordshire. RSWs are inter-disciplinary in their breadth: from history to political economy, demography to linguistics, anthropology to geography. They often include in-depth case studies from areas of historic and expanding military presence: Afghanistan and Pakistan; the Balkans and the Baltics; Egypt, Palestine and Israel; Iran, Iraq, Syria and Yemen; Kenya and Somalia on the Horn of Africa, Nigeria and Mali on the West Coast. Each session allows half an hour for military personnel to ask academics questions, including on potential "next flashpoints" or "conflict scenarios." Most weeks end with an explicit session, or entire day, on the specific “implications for UK military missions,” or "practical exercises involving issues likely to be encountered by MoD staff."

SOAS procures ‘experts’ predominantly from its own academic staff to facilitate these trainings, although other university faculty are often involved, including from LSE, St Andrews, Cambridge, King's College London, UCL, Lancaster, De Montfort, as well as military consultants such as IHS Markit and right-wing foreign policy think tanks like Chatham House.

SOAS’ official response to our initial publication in July 2019 claimed that, because it takes a Critical and non-Eurocentric stance in relation to our regions," it is "right and important that such perspectives are brought to bear on bodies which are engaged with these regions." The legitimacy of British military ‘engagement’ with ‘bodies’ in Africa or anywhere else is implicitly assumed, alongside the possessive impulse to extract knowledge from the global South for British military consumption.

SOAS has aggressively cut courses and languages that focus on Africa, leading to student campaigns such as ‘where is the A in SOAS?’ and Art and the African Mind to resist institutional anti-Black racism. For this reason alone, SOAS’ trainings on ‘sub-Saharan Africa’ are of relevance for further scrutiny. In both RSWs to date, military personnel were briefed on themes such as African history, which in characteristic colonial revisionism begins in the 19th century, as well as ‘understanding African leaders and hierarchies,’ and ‘corruption, patronage and clientelism.’ Out of eleven individuals employed to deliver these briefings, only one is of African descent, while seven were white men, including SOAS Emeritus Professor Jeremy Keenan and Phil Clark, recently promoted to Professor of International Politics, who leads the section.

Clark, who has proudly confirmed his participation in the trainings on Twitter, has stated his sessions focus, in particular, on “demythologising the MoD’s glowing narrative of the British army’s intervention in Sierra Leone” under Blair’s Labour government, alerting military personnel to the issues that “affect their work and the MoD’s likely impact on the places where it intervenes.” Important to include, we assume, would be the centuries of colonial violence and resource extraction which fuelled and followed Britain’s intervention in the civil war. Perhaps he also mentioned another cyclical link to SOAS after major rutile miner Titanium Resources Group, which accounts for around 65% of Sierra Leone’s exports, appointed departing SOAS director Valerie Amos as a non-executive director in 2008, a position from which she later resigned.

Secondly, Professor Friederike Luepke, who Art and the African Mind have documented making racist remarks about a Black student, delivered four hours of DCSU briefings on “sources of identity: kinship, race, ethnicity and nationalism in West Africa.” This is important to place in the context of the MoD’s announcement in August that another 250 British ground troops will be deployed to Mali in 2020, joining over 100 RAF personnel as well as three Chinook helicopters already present in the country to support the French-led military coalition of 12,500 combat troops in the Sahel region.8 Weapons and armaments have flooded the Sahel since the catastrophic NATO invasion of Libya led by America, Britain and France, making it a focal point of imperial aggression, as well as a source to trans-Saharan migration routes towards the world’s deadliest border-crossing, Fortress Europe.

Finally, in ‘Something Torn and New,’ Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o articulates the power of naming, how it serves to appropriate and demonstrate who has authoritative power by marking out their territory. It has been argued extensively that the regional categories SOAS imposes should themselves be seen as colonial legacies rooted in racism, and the convenience and gaze of imperial strategists and military planners, with the severing of Africa between ‘North’ and ‘Sub’ often used to imply that the former is more advanced because of its closer proximity to Europe (and therefore whiteness). In his open letter response to our campaign, Professor Gilbert Achcar, who has delivered nearly 28 hours of training over two separate RSW’s on the ‘Middle East and North Africa’, called this as a “most absurd accusation that…require(s) no further comment,” rallying around a “sensible geopolitical consideration” evidenced by the unfolding of the “Arab Spring.” By overlooking the trades, languages, and religions which have crossed the desert over centuries, as well as the many African peoples—from the Nubian and Amazigh to the Tuareg—who lived and continue to live in northern Africa, including their participation in revolutions past and present, it is disappointing that Professor Achcar instead defends the categories imposed by European empires to divide and rule the continent.

Academia and the “future character of conflict”

As militarism adapts and evolves with industry and automation, alongside the lithium-ion tanks and solar-powered drones, the ‘hearts and minds’ of people subjugated and terrorised by war are also increasingly in demand.The DCSU was formed in 2010 in response to the invasions and occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan. Mike Martin, an Officer in Helmand Province, was frustrated by the ignorance of the occupying forces and their misinterpretation of the conflict. Martin is said to have pioneered, designed and implemented the role of ‘Cultural Advisor’ and the ‘Human Terrain Mapping Unit.' He went on to write ‘An Intimate War’ for his PhD at KCL, a critical account of the UK’s approach in Afghanistan that the MoD tried to block from being published. He is now a research fellow in the War Studies Department at KCL. In the same year, the Iraq Historic Allegations Team and Operation Northmoor were established to investigate alleged war crimes by British soldiers in those countries; both ended without prosecutions, abandoning numerous cases due to insufficient resources and institutional cover-ups.

Having neutralised accountability and incorporated internal dissent, the MoD describes the DCSU as its “centre of excellence for cultural capability” in a 2013 Doctrine Note which emphasises the “significance of culture to the military." The MoD argues that because "success in operations relies on a measure of compliance and support from the local population," cultural specialists are expected to "actively gather human terrain and cultural information" explicitly intended to help "plan and execute military operations."

The note is also explicit about drawing specialists from the academy: individuals "who have expert or intimate knowledge of the region," making them able to "prepare" the military to "engage with the population" by, for example, providing insights into how a population "might react to destroying or protecting a particular target." Ironic examples of the kinds of behaviour these ‘specialists’ are advised to report on, the MoD twice refers to the British convention of queuing, attributing a cultural predisposition for waiting patiently to a country that has pillaged and plundered the world for centuries.

However, the DCSU is only one of nineteen units operating under the 1st Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Brigade, which sits alongside four other brigades in the 'modernised' 6th Division of the UK Armed Forces. The DCSU's brigade is responsible for all British army’s “electronic warfare and signals intelligence; surveillance and target acquisition patrols; and unmanned aerial systems.” In the Force Troops Command handbook, the DCSU, alongside other branches of military intelligence, form the ‘Information Manoeuvre’ taskforce oriented towards “attack(ing) the enemy’s cohesion and willingness to fight, rather than simply destroying their capability.” This casts the DCSU in a “unique position,” according to the Doctrine Note, with a “central contribution” to Britain’s military footprint.

|

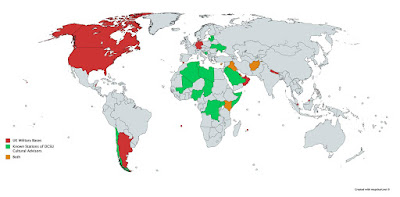

| Locations of British Military presence: Red for military bases, Green for DCSU cultural advisors, orange for both |

The DCSU pamphlet states it provides cultural specialists “to support operations, Defence Engagement and wider military taskings anywhere in the world, on land and at sea.” It “develops and supports” this doctrine “across Defence,” offering “bespoke service to deploying units, teams and individuals.” This ranges from country briefs, presentations and analysis of the ‘human terrain’ to “advising the Command on the cultural and local impact of planned actions and building relations with the local population.” As of 2016, the DCSU had been served by at least 64 regular Cultural Advisors (and 26 reserves) in at least 22 countries (see map).

It is important to note that US Military formed the “Human Terrain System” in the same context, employing anthropologists to work with soldiers in Afghanistan. The American Anthropologist Association widely condemned this program at the time for violating the ethical imperative to “do no harm to those they study”. As part of the Network of Concerned Anthropologists formed to demand that Congress halt funds for HTS, Professor David Price argued that, far from being a “neutral humanitarian project,” the HTS functions as an “arm of the US military” and must therefore be seen as part of “the military’s mission to occupy and destroy opposition to US goals and objectives.” Its goal, their open letter asserted, is simply a “gentler form of domination.” Despite reproducing similar patterns of domination, the emergence of the DSCU, let alone the role of academic institutions in facilitating and profiting from its growth, has attracted negligible public scrutiny in comparison.

To be clear, SOAS’ collaboration with the DCSU does not offend the historical function of this university or any essential values that the institution projects for itself in marketing brochures: SOAS has always been a hub for the British military establishment and produced knowledge in the service of empire-building. It does, however, reveal the devastating hypocrisy of an institution that claims to decolonise in public while briefing the military in private. We demand that SOAS cancels its contract with the MoD and call on other universities not to collaborate with the military and arms industries. We demand an education system that cultivates spaces where we, understood in the most expansive sense, are empowered to rediscover, imagine and create worlds that renew life and nature, rather than war and destruction.

1 Belcher, Oliver, Patrick Bigger, Ben Neimark, and Cara Kennelly (2019). ‘Hidden carbon costs of the “everywhere war”: Logistics, geopolitical ecology, and the carbon boot-print of the US military,’ Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers.

2 Greg Muttit (2012). Fuel on the Fire: Oil and Politics in Occupied Iraq.